This robot automatically tucks its limbs to squeeze through spaces

Inspired by how ants move through narrow spaces by shortening their legs, scientists have built a robot that draws in its limbs to navigate constricted passages.

The robot was able to hunch down and walk quickly through passages that were narrower and shorter than itself, researchers report January 20 in Advanced Intelligent Systems. It could also climb over steps and move on grass, loose rock, mulch and crushed granite.

Such generality and adaptability are the main challenges of legged robot locomotion, says robotics engineer Feifei Qian, who was not involved in the study. Some robots have specialized limbs to move over a particular terrain, but they cannot squeeze into small spaces (SN: 1/16/19).

“A design that can adapt to a variety of environments with varying scales or stiffness is a lot more challenging, as trade-offs between the different environments need to be considered,” says Qian, of the University of Southern California in Los Angeles.

For inspiration, researchers in the new study turned to ants. “Insects are really a neat inspiration for designing robot systems that have minimal actuation but can perform a multitude of locomotion behaviors,” says Nick Gravish, a roboticist at the University of California, San Diego (SN: 8/16/18). Ants adapt their posture to crawl through tiny spaces. And they aren’t perturbed by uneven terrain or small obstacles. For example, their legs collapse a bit when they hit an object, Gravish says, and the ants continue to move forward quickly.

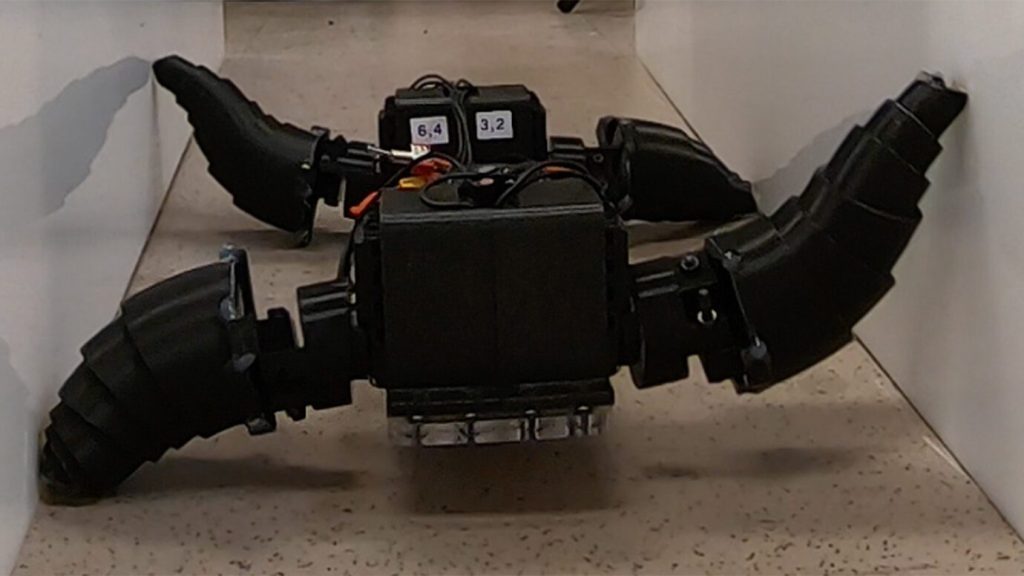

Gravish and colleagues built a short, stocky robot — about 30 centimeters wide and 20 centimeters long — with four wavy, telescoping limbs. Each limb consists of six nested concentric tubes that can draw into each other. What’s more, the limbs do not need to be actively powered or adjusted to change their overall length. Instead, springs that connect the leg segments automatically allow the legs to contract when the robot navigates a narrow space and stretch back out in an open space. The goal was to build mechanically intelligent structures rather than algorithmically intelligent robots.

“It’s likely faster than active control, [which] requires the robot to first sense the contact with the environment, compute the suitable action and then send the command to its motors,” Qian says, about these legs. Removing the sensing and computing components can also make the robots small, cheap and less power hungry.

The robot could modify its body width and height to achieve a larger range of body sizes than other similar robots. The leg segments contracted into themselves to let the robot wiggle through small tunnels and sprawled out when under low ceilings. This adaptability let the robot squeeze into spaces as small as 72 percent its full width and 68 percent its full height.

Next, the researchers plan to actively control the stiffness of the springs that connect the leg segments to tune the motion to terrain type without consuming too much power. “That way, you can keep your leg long when you are moving on open ground or over tall objects, but then collapse down to the smallest possible shape in confined spaces,” Gravish says.

Such small-scale, minimal robots are easy to produce and can be quickly tweaked to explore complex environments. However, despite being able to walk across different terrains, these robots are, for now, too fragile for search-and-rescue, exploration or biological monitoring, Gravish says.

The new robot takes a step closer to those goals, but getting there will take more than just robotics, Qian says. “To actually achieve these applications would require an integration of design, control, sensing, planning and hardware advancement.”

But that’s not Gravish’s interest. Instead, he wants to connect these experiments back to what was observed in the ants originally and use the robots to ask more questions about the rules of locomotion in nature (SN: 1/16/20).

“I really would like to understand how small insects are able to move so rapidly across certain unpredictable terrain,” he says. “What is special about their limbs that enables them to move so quickly?”