Cave art suggests Neandertals were ancient humans’ mental equals

Neandertals drew on cave walls and made personal ornaments long before encountering Homo sapiens, two new studies find. These discoveries paint bulky, jut-jawed Neandertals as the mental equals of ancient humans, scientists say.

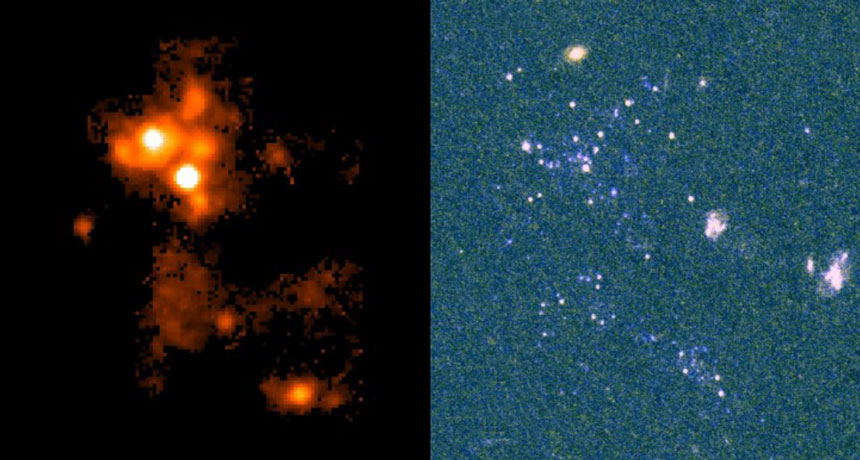

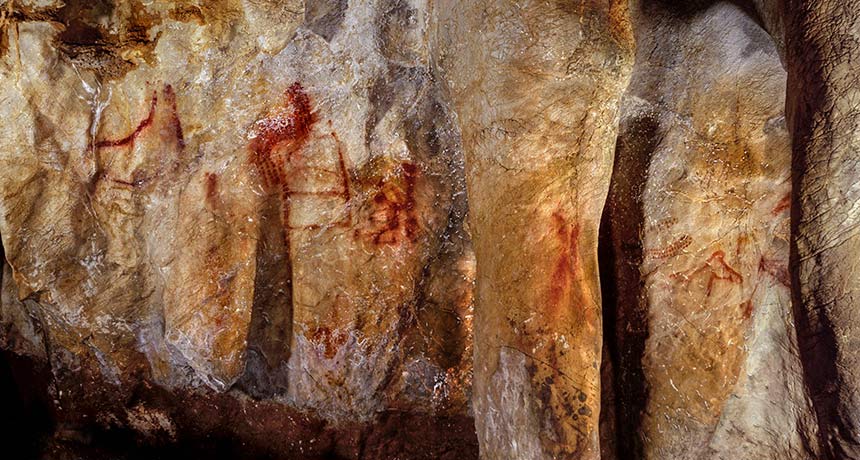

Rock art depicting abstract shapes and hand stencils in three Spanish caves dates back to at least 64,800 years ago, researchers report in the Feb. 23 Science. If these new estimates hold up, the Spanish finds become the world’s oldest known examples of cave art, preceding evidence of humans’ arrival in Europe by at least 20,000 years (SN Online: 11/2/11).

The finds raise the possibility that “Neandertals took modern humans into caves and showed them how to paint,” says archaeologist Francesco d’Errico of the University of Bordeaux in France.

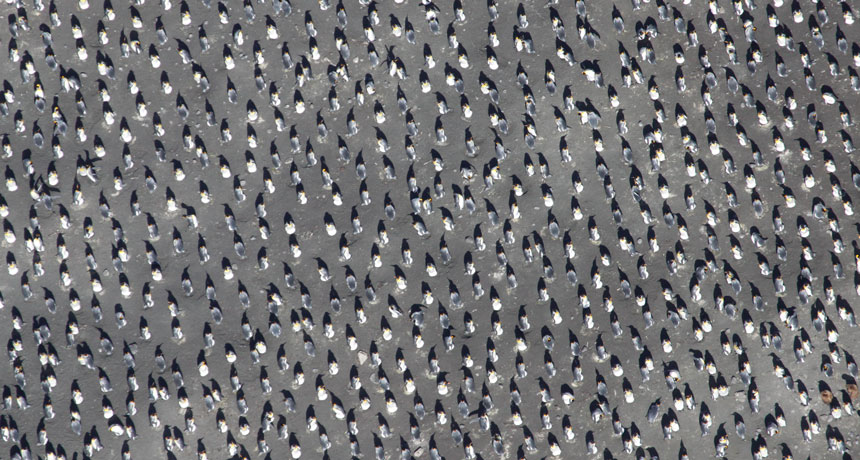

Personal ornaments previously found at a coastal cave in southeastern Spain are older than the cave art, dating to around 120,000 to 115,000 years ago, scientists report February 22 in Science Advances. Only Neandertals inhabited Europe at that time. Those artifacts consist of pigment-stained seashells with artificial holes, presumably for use as necklaces, and seashells containing remnants of pigment mixtures, say geochronologist Dirk Hoffmann of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, and colleagues. Hoffmann is also an author of the cave art study. The new findings join previous reports of potentially symbolic Neandertal artifacts, such as a possible necklace made from eagle claws (SN: 4/18/15, p. 7) and bird-feather decorations.

If Neandertals did have the capacity for symbolic thinking — crucial for using drawings or language to represent ideas and objects — that ability may have developed at least 500,000 years ago in an ancestor shared with humans, the two research teams propose.

“Neandertal social life was as complex as that of [contemporaneous] humans in Africa,” says archaeologist João Zilhão of the University of Barcelona, an author of both papers.

But some scientists view the new findings cautiously. Neandertals communicated in sophisticated ways, but few clearly symbolic artifacts have been linked to them, says archaeologist Nicholas Conard of the University of Tübingen in Germany. “If Neandertals regularly produced paintings or similar kinds of symbolic artifacts, researchers will eventually demonstrate it at multiple sites,” he says.

Analyses of thin mineral deposits partly covering painted cave areas provided minimum age estimates for the art, based on known decay rates of radioactive uranium in the rock. One red, rectangular painting dates to at least 64,800 years ago. One of several hand stencils in a second cave dates to at least 66,700 years ago. And in a third cave, patches of red paint were applied to the walls at least 65,500 years ago, with more paintings added over a period of 25,000 years or more — signaling a long Neandertal tradition of cave art, the researchers say.

Many dated deposits at the Spanish cave art sites contain rock particles from external sources that can throw off age estimates. The researchers statistically corrected for such contamination, “but whether that is sufficient enough remains to be seen,” says archaeologist Katerina Douka of the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Jena, Germany.

At the coastal cave, dating relied on a one-two punch: uranium analyses of rock partly covering shell-bearing sediment and geologic estimates of when ancient sea levels declined enough to allow entry into the chamber.

Still, it is “nearly impossible” to generate accurate age estimates of rock art based on uranium measures alone, researchers concluded in 2017 in Quaternary International. Depending on shifting cave conditions and varying amounts of uranium drainage from mineral deposits, this method can over- or underestimate when rock art was created, the scientists argued. Other researchers defend this technique as providing valuable minimum and maximum age estimates for rock art.

If the new dates for the Spanish cave art are confirmed, they could indicate that Neandertals and H. sapiens exchanged artistic traditions earlier than previously thought, says paleoanthropologist Chris Stringer of the Natural History Museum in London, who was not involved in the studies. Members of both species may have reached western Asia and intermingled during rainy periods between 244,000 and 190,000 years ago, Stringer proposes (SN: 2/17/18, p. 6).