Enabling villagers to live a more comfortable life

"We are truly grateful for the policy of the Party, which encourages farmers to develop forestry to alleviate poverty and become prosperous," said Huang Chuanrong, a farmer in Ningde, East China's Fujian Province, who succeeded in escaping poverty through planting.

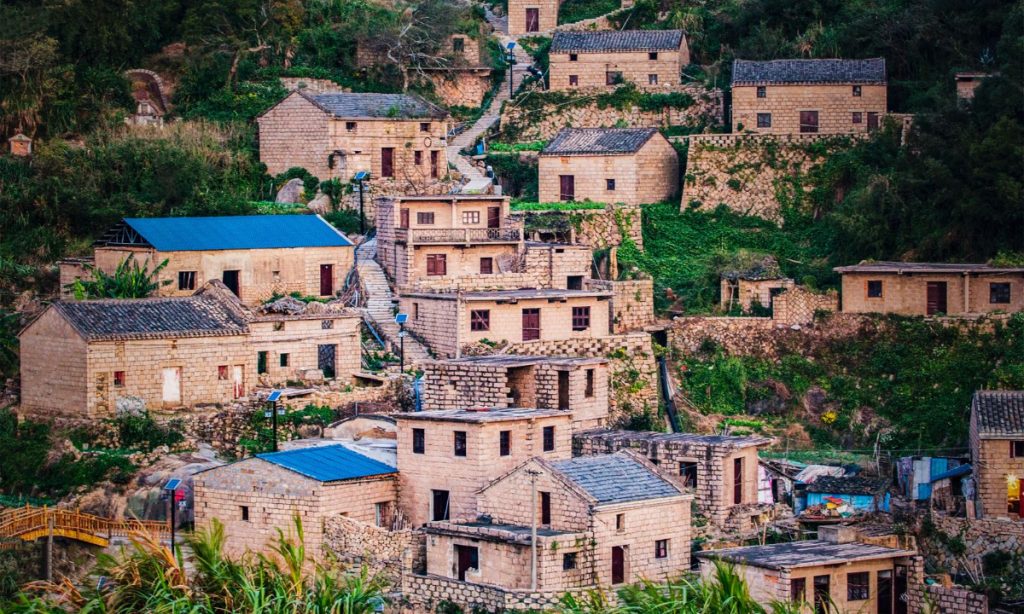

Ningde is a city located in the northeast part of Fujian Province, with a land area of 13,400 square kilometers. It used to be one of the 18 concentrated and contiguous poverty-stricken areas in the country, making it the dream of the people in the region to overcome poverty and live a comfortable life.

The land of eastern Fujian has undergone great changes and has become a model of poverty alleviation with Chinese characteristics. For decades, the Ningde model of precise poverty alleviation has been formed through unremitting efforts from the grassroots officials and masses.

Enduring efforts

Houyang village is located in Zhouning county in Ningde. The family forest farm initiated by the elderly Huang Zhenfang has not only created a unique path to prosperity through forestry but has also made outstanding contributions to regional afforestation.

"Before the policy of reform and opening-up, our family was very poor. My elderly father was a thin and weak farmer. Since I was 13 years old, I have been helping my father in the fields, hoping to lighten the burden on our family," Huang Chuanrong, Huang Zhenfang's son, told the Global Times.

According to Huang, at that time, there were hardly any trees in the village, and soil erosion was very severe, with heavy rain often causing landslides.

"We really appreciate the Party's policy," Huang sincerely told the reporter, expressing that the opportunity to establish a family forest farm originated from the Party's guiding policy for the benefit of the people.

In 1983, Huang Zhenfang led his whole family to embark on the path of afforestation and land reclamation under the guidance of "No.1 central document." It took three years for the afforestation area to expand from the original 50 mu (3.3 hectares) to 1,207 mu.

"We received recognition from the county Party committee and government, and the villagers saw the positive results coming from the policy of the Party and joined us one after another," Huang Chuanrong said.

However, the development of forestry has the problem of long growth cycles and slow returns.

"To solve the problem of funding shortages, my resourceful grandfather started trying intercropping potatoes, corn, konjac, and tea in the forest, using the short-term growing crops to support the long-term development of the trees. This not only increased the family income but also effectively utilized land resources, improving our family's life as well," Huang Chuanrong's daughter Huang Juanjuan told the Global Times.

At the same time, the quality of the soil improved due to the use of fertilizers for crop cultivation. "It was truly a remarkable idea," she said.

Currently, the Huang family's household forest farm still regards agricultural production as its main business. They cultivate over 100 mu of medicinal herbs such as Huangjing, raise 200 beehives, and grow crops like sweet potatoes.

Their annual income exceeds 300,000 yuan ($42,000), and they have helped more than 50 villagers to become prosperous.

The story of Huang Zhenfang's forest farm has deeply influenced the descendants of the Huang family. Huang Yubin, the grandson of the resourceful elderly man, has helped promote the agricultural and forestry products of Zhouning to a broader market through the development of e-commerce, further consolidating the poverty alleviation achievements of the village.

According to Huang Yubin, he returned to his hometown to start a business in 2021 and established a company focusing on e-commerce in January 2023, listing more than 20 agricultural, forestry, and cultural products. Huang is currently connecting with relevant companies in Fujian Province, trying to use livestreaming to promote sales.

"I used to be a designer, so I thought of creating cultural and creative products, such as turning the herbal medicines into sachets and selling them online," he told the Global Times, expressing his pride in using his expertise to contribute to the revitalization of his hometown.

More rural revitalization channels

There are more cases in Ningde city to promote rural revitalization. Gutian county is the largest edible fungi production base in the country. Since 2012, the county Party committee and government have made efforts to promote the transformation and upgrading of the edible fungi industry.

Among them, one important aspect is to improve the cultivation conditions of edible fungi, aiming to solve the safety hazards and high labor intensity of grass mushroom shed.

After in-depth research on farmers and combining various biological characteristics of edible fungi with current production technologies at home and abroad, a series of edible fungi mushroom shed types have been designed for farmers to choose from.

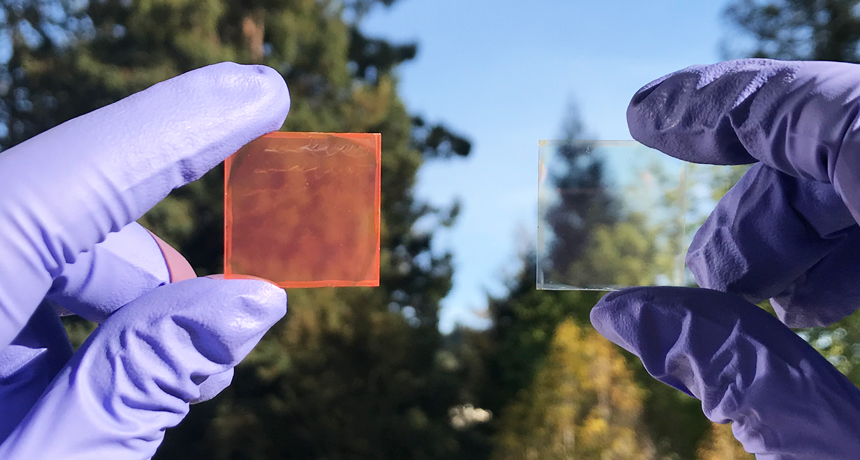

Constructing photovoltaic mushroom sheds is an important path to explore the combination of the edible mushroom industry and the new photovoltaic industry. It is also an important measure to reduce the cost of standardized mushroom shed transformation for mushroom farmers.

According to Zheng Kuidong, deputy secretary of the county Party committee, since May 2021, a total of nine photovoltaic mushroom shed projects have been implemented in the county. After the completion of the projects, it is estimated that 37,058.4 tons of water can be saved and 23,761.9 tons of carbon dioxide emission can be reduced annually.

"Photovoltaic mushroom sheds can effectively achieve the generation of green electricity and the cultivation of high-quality mushrooms," Zheng told the Global Times.

"Traditional mushroom sheds are made of wooden boards. The conditions of photovoltaic mushroom sheds have improved significantly because they are not affected by typhoons and can maintain a stable temperature range suitable for mushroom growth," Yu Xinkao, a local mushroom farmer, told the Global Times.

He added that the improved conditions of the sheds have significantly increased mushroom production. Yu also mentioned that when encountering technical difficulties, there are designated government workers who can be contacted to provide on-site assistance.

According to Zheng, the county promotes rural revitalization through various channels such as increasing income for mushroom farmers, operating and managing cooperatives led by Party branches, and connecting production and sales through large-scale commercial supermarkets of leading enterprises. "I have great confidence in the continued development of photovoltaic mushroom sheds in the future," Yu said.