Smart windows could block brightness and harness light

Who needs curtains? One day, you could block out afternoon glare and heat with changeable windows that absorb sunshine to charge your electronics.

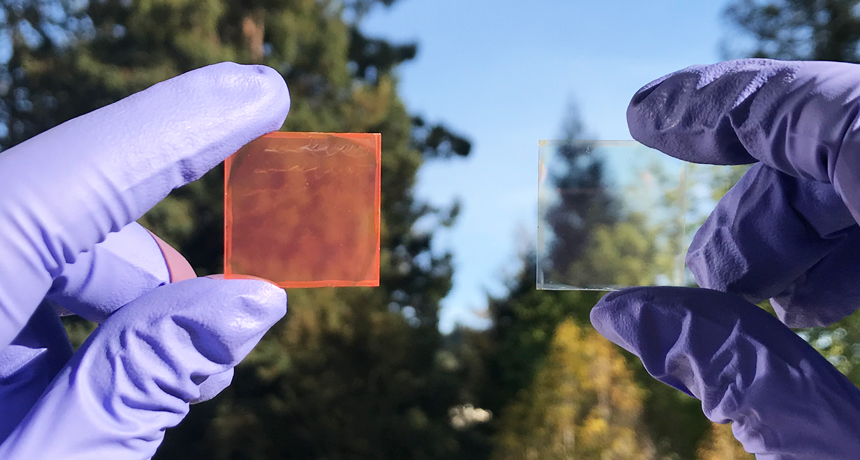

A high-tech prototype panel described online January 22 in Nature Materials, switches between transparent pane and dark-tinted solar cell. The layer in the panel that’s responsible for soaking up sun has atoms that only arrange themselves into a light-absorbing crystal structure at high temperatures. When heated, these atoms form a dark-tinted crystal known as a perovskite, a new darling of the solar cell industry (SN: 8/5/17, p. 22).

Letian Dou, a chemical engineer at Purdue University, and colleagues were only able to form these light-harvesting crystals in their solar cells by cranking the heat to 105° Celsius, much hotter than your average sun-blasted window. The team is working to lower that threshold to below 70° C so that sunshine alone would trigger the switch.

Currently, the perovskite’s atoms stay locked in crystal configuration until exposed to moisture, which jumbles up the atoms and turns the material transparent again. The researchers still need to find a way to deactivate the solar cell mode without needing a spray bottle of water on hand.

The technology could someday be used for windshields that recharge electric vehicles and keep a parked car’s interior cool while the sun bakes outside.